When Play Looks Like Learning: The Science Behind Play-Based Development

Discover why play is not the opposite of learning but the most powerful driver of cognitive, social, and emotional development in early childhood.

Twenty-month-old Sofia toddles through the living room, points at the family dog, and says "perro." Her grandmother, visiting from Mexico, beams with pride. Sofia's mother, however, feels a familiar knot of anxiety. At playgroup yesterday, the other toddlers were chattering in full sentences while Sofia mixes Spanish and English, using maybe fifteen words total. One well-meaning mom asked, "Have you thought about just sticking to English until she catches up?"

This is the moment of doubt that haunts countless bilingual families. Are we doing the right thing? Are two languages too much? Is our beautiful cultural gift to our daughter actually holding her back?

Sofia's mother isn't alone in this worry. Parents raising children in bilingual or multilingual environments face constant questions—from relatives, pediatricians, preschool teachers, and other parents—about whether exposing young children to multiple languages causes confusion, delays speech development, or creates learning difficulties. The concern feels especially urgent when a bilingual toddler speaks later than monolingual peers or mixes languages in the same sentence.

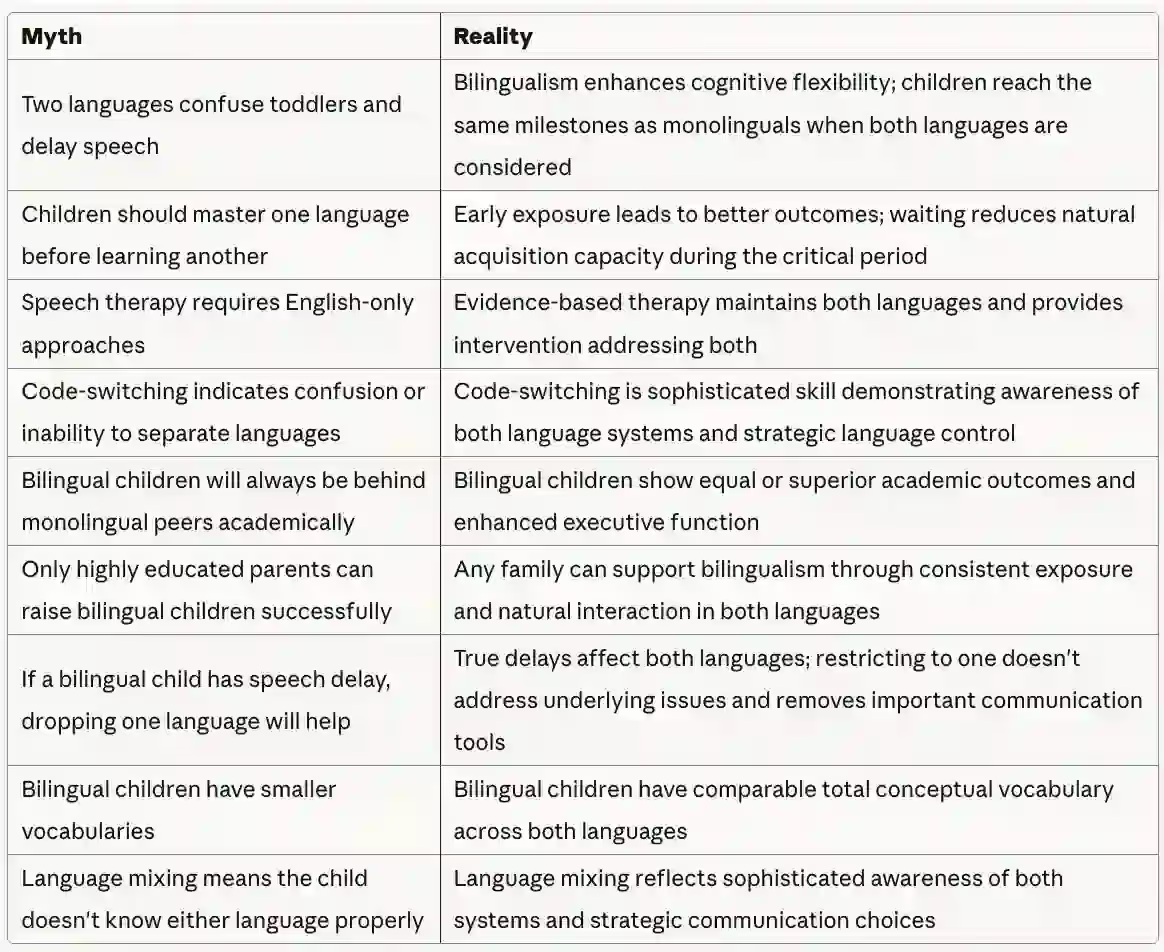

Here's what you need to know immediately: The scientific consensus is clear—bilingualism does not cause speech delay. Decades of research across linguistics, developmental psychology, and neuroscience consistently show that learning two languages simultaneously is well within typical human capacity and doesn't impair language development. In fact, bilingualism confers significant cognitive advantages that extend far beyond language itself.

But this answer, while true, doesn't address all the nuances parents need to understand. Why do some bilingual toddlers seem to talk later? How can you tell the difference between normal bilingual development and actual speech delay requiring intervention? What does healthy bilingual language acquisition look like at different ages? And how can parents best support children learning multiple languages?

This article breaks down the science of bilingual speech development, distinguishes normal bilingual patterns from concerning delays, addresses common myths, and provides practical, evidence-based strategies for supporting your child's multilingual journey. Whether you're already raising a bilingual child or considering introducing a second language, you'll understand what to expect, when to worry, and how to provide the best possible language environment for your child's developing brain.

Before addressing concerns about delay, it's essential to understand what researchers and clinicians know about how bilingualism works in developing minds.

Defining bilingualism in childhood requires distinguishing between simultaneous and sequential bilingual exposure. Simultaneous bilinguals are exposed to two languages from birth or within the first year of life—these are children like Sofia whose families speak different languages at home. Sequential bilinguals learn a second language after establishing a first language, typically after age three—for instance, children who speak Spanish at home and begin learning English when entering preschool.

Most concerns about speech delay focus on simultaneous bilinguals, though both pathways produce fully bilingual, cognitively healthy individuals when properly supported.

The scientific consensus from major professional organizations is unambiguous and reassuring. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), the primary professional organization for speech-language pathologists in the United States, clearly states that bilingualism does not cause speech or language disorders. Children can learn two languages as easily as one, and being bilingual is not the cause of language delays.

The American Psychological Association similarly affirms that bilingual children develop language at the same rate as monolingual children, though the process may look different superficially. Research tracked across decades and countless studies consistently demonstrates that bilingual children reach the same language milestones as monolingual peers when both languages are considered together.

The key insight—and the source of much parental confusion—is that bilingual children's language abilities must be assessed cumulatively across both languages, not separately in each. A bilingual toddler with 30 words in English and 25 words in Spanish has a vocabulary of 55 words total, comparable to or exceeding the monolingual child with 50 English words. Evaluated only in English, however, that same bilingual child appears behind, creating false impression of delay.

The developing bilingual brain doesn't maintain two completely separate language systems. Instead, neurological research shows that bilinguals develop an integrated language system with shared underlying concepts and executive control mechanisms allowing them to select appropriate language for each context. This integration is sophisticated and develops naturally through exposure—children don't need explicit instruction about which language to use when. They naturally map words from both languages onto the same concepts and learn through social cues which language to use with which people.

Understanding these foundations helps parents recognize that bilingual development, while sometimes appearing different from monolingual patterns, is normal, healthy, and cognitively sophisticated rather than confusing or problematic.

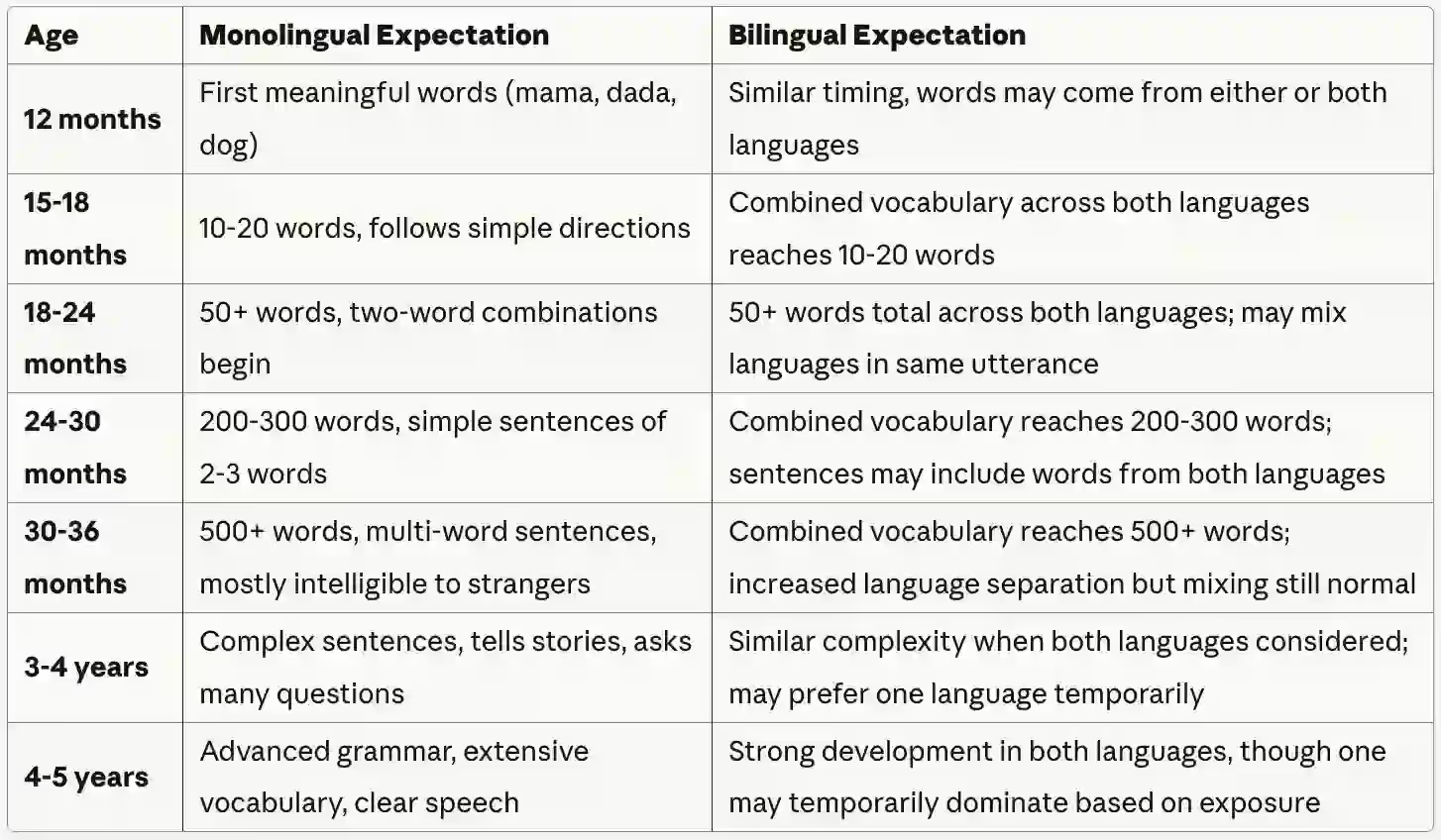

Knowing what to expect at each age helps distinguish typical development from concerning delays.

According to CDC developmental milestones, these ranges represent typical development, though individual variation is normal and children may reach milestones slightly earlier or later without concern.

Key differences in bilingual development:

The critical principle for parents to understand is that total language development matters more than individual language progress. If your bilingual child has age-appropriate combined language abilities across both languages, they're developing normally even if they appear behind when assessed in only one language.

Understanding why bilingual development sometimes looks different from monolingual patterns helps reduce parental anxiety and prevents unnecessary interventions.

Vocabulary is distributed across two languages, creating the illusion of smaller vocabulary in each. A 24-month-old monolingual child might have 100 English words. A bilingual child the same age might have 60 English words and 50 Spanish words—110 total, actually slightly ahead, but appearing behind in English when evaluated separately. Pediatricians, teachers, or relatives unfamiliar with bilingual development may see the 60 English words and recommend concern, when the child is actually developing beautifully.

Code-switching is mistaken for confusion by adults who don't understand bilingualism. When toddlers mix languages—"Look at the perro!"—many people interpret this as inability to keep languages separate or confusion about which language is which. Research published in outlets like PubMed shows that code-switching is actually a sophisticated linguistic skill requiring awareness of both language systems and strategic choices about which words to use. Children code-switch because it's efficient—they're using whatever word comes to mind first or conveys meaning most precisely, demonstrating flexibility rather than confusion.

Slower start, faster catch-up characterizes some bilingual children's expressive language development. Some bilingual toddlers speak slightly later than monolingual peers, particularly if exposure to each language is relatively balanced rather than heavily weighted toward one. However, once they begin speaking, they typically catch up rapidly and often surpass monolingual peers in total language development by preschool age. The brief delay reflects the cognitive work of managing two systems, but doesn't indicate problems.

Translanguaging—using features from both languages fluidly as integrated communication—is increasingly recognized as normal bilingual practice rather than deficit. Bilingual children naturally draw on their full linguistic repertoire, and research shows this integration reflects cognitive sophistication rather than inability to separate languages. Traditional views treating language mixing as problematic are being replaced by understanding that bilingual brains naturally function this way.

Interference between languages occurs when sounds, grammatical structures, or vocabulary from one language influence production in the other. A Spanish-English bilingual child might say "I putted" (overapplying English regular past tense) or produce Spanish /r/ sounds in English words. This isn't confusion—it's natural transfer that resolves as experience with each language increases. Monolingual children make similar errors within single languages as they learn grammatical rules.

Comparison to monolingual peers creates false impressions of delay when bilingual children are evaluated against monolingual norms. The child at playgroup producing longer English sentences than Sofia isn't necessarily more linguistically advanced—they're just focusing all language development on one language while Sofia is developing two. If that monolingual child were simultaneously learning Spanish, their English might look similar to Sofia's.

These patterns don't indicate problems requiring intervention. They're normal features of acquiring two languages simultaneously, and they resolve naturally with continued exposure and development.

While concerns about delay get attention, bilingualism's cognitive advantages deserve equal emphasis because they're substantial and well-documented.

Improved executive function represents bilingualism's most researched advantage. Executive functions—working memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and attention control—develop more strongly in bilingual children compared to monolingual peers. Research from Harvard's Center on the Developing Child shows that managing two languages requires constant executive control—deciding which language to use, suppressing one while using the other, switching between languages when context changes. This daily workout strengthens executive function capacities that extend beyond language.

Bilingual children show advantages in tasks requiring attention control, such as focusing on relevant information while ignoring distractions. They demonstrate better inhibitory control, successfully suppressing automatic responses when circumstances require different actions. They exhibit enhanced cognitive flexibility, more easily shifting between different tasks or ways of thinking. These advantages emerge in early childhood and persist through adolescence and adulthood.

Enhanced problem-solving abilities appear in bilingual children starting in preschool years. Bilinguals show more creative approaches to problems, generate more diverse solutions, and demonstrate better skills in tasks requiring thinking about things in multiple ways. The experience of expressing the same concept in two different languages seems to support understanding that problems can have multiple solutions and that there are different valid approaches to challenges.

Metalinguistic awareness—the ability to think about language as an object of analysis—develops earlier and more strongly in bilingual children. They understand earlier that words are arbitrary labels for concepts, that the same concept can be expressed differently, and that language systems have rules that can be examined. This awareness supports literacy development, language learning generally, and even mathematical reasoning, which requires similar abstract thinking about symbols and systems.

Advanced theory of mind and perspective-taking emerge earlier in bilingual children. Theory of mind—understanding that other people have thoughts, beliefs, and perspectives different from your own—is crucial for social development. Bilingual children, who constantly navigate which language different people speak and adjust their language accordingly, develop stronger understanding of others' mental states. They recognize earlier that people have different knowledge and perspectives, supporting empathy and social competence.

Long-term academic advantages follow from these cognitive benefits. Bilingual children often show advantages in reading comprehension, abstract thinking, and learning additional languages later. The cognitive flexibility, metalinguistic awareness, and executive function skills developed through bilingualism support academic learning across domains, not just language arts.

Protective effects against cognitive decline in later life have been documented in research with bilingual adults, suggesting that early bilingualism creates cognitive reserve that benefits people throughout the lifespan. While this doesn't directly concern parents of toddlers, it underscores that bilingualism is a gift with lifelong value.

These benefits aren't just theoretical—they're measurable cognitive advantages that support children's development across domains. Even if bilingualism caused slight delays (which research shows it doesn't), the cognitive advantages would still make it worthwhile. But since bilingualism doesn't delay language development while providing substantial cognitive benefits, it's genuinely advantageous without trade-offs.

This is the crucial question for worried parents: can bilingualism cause actual speech delay requiring intervention?

The clear answer from decades of research and clinical practice is: bilingualism alone does not cause true speech or language delay. Speech and language disorders occur at the same rates in bilingual and monolingual children. When bilingual children have genuine speech delays, bilingualism isn't the cause—there's an underlying condition or developmental issue that would exist regardless of language environment.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children who have difficulty with language development will have that difficulty in all languages they're exposed to. A true language delay affects underlying language capacity, not just one language. If a bilingual child is developing slowly in one language but progressing well in the other, that's not language delay—that's differential exposure or preference, which is normal.

Speech disorders including articulation problems, phonological disorders, and stuttering occur at similar rates in bilingual and monolingual populations. A child who stutters might stutter in both languages, or might stutter more in one than the other based on comfort level and exposure, but bilingualism didn't cause the stuttering. A child with difficulty producing certain sounds will have articulation challenges that may manifest differently across languages based on which sounds each language uses, but the underlying speech motor difficulty exists independently of bilingualism.

Language disorders affecting vocabulary, grammar, comprehension, or expression similarly occur independently of bilingual exposure. Children with specific language impairment (SLI) or other language-based learning differences will show difficulties across both languages, though the specific manifestations might differ based on how each language works structurally.

When bilingualism appears linked to delay, other factors are usually responsible:

Supporting healthy bilingual development requires understanding and implementing strategies that provide rich exposure in both languages while maintaining natural communication.

The One-Parent-One-Language (OPOL) approach involves each parent consistently speaking a different language to the child. Mom always speaks Spanish, Dad always speaks English, and the child hears both languages from birth through consistent sources. This provides clear language models and natural separation that can support acquisition. However, OPOL requires that both parents have native or near-native proficiency in their assigned language and can maintain consistency across contexts. When implemented well, OPOL produces strong bilingual development.

Potential challenges with OPOL include difficulty maintaining strict separation in all contexts, potential for one language to dominate if that parent spends more time with the child, and situations where parents speak each other's languages fluently making strict separation feel artificial. These challenges don't mean OPOL doesn't work, just that flexibility and adaptation may be necessary.

The Minority Language at Home strategy involves speaking the non-community language exclusively or primarily at home while allowing the majority community language to develop through school, media, and broader social contexts. For English-speaking families in the United States raising children with Spanish, French, or another heritage language, this might mean Spanish at home with English entering through preschool and community.

This approach recognizes that majority languages typically receive ample external support while minority languages need intentional protection and promotion. The challenge is ensuring children receive sufficient majority language exposure for school readiness, which typically happens naturally through educational settings and media once children reach preschool age.

Time and place strategies involve using one language in certain contexts or times. "Spanish at dinner" or "French on weekends" or "Mandarin at grandparents' house" creates predictable patterns. While less consistent than OPOL, these approaches can work when full bilingualism isn't feasible but families want significant second language exposure.

Daily routines incorporating both languages provide natural contexts for rich language input. Morning routines, mealtimes, bath time, and bedtime offer predictable, repeated activities perfect for language learning. Narrating these routines—"Let's wash your hands," "Time to brush teeth"—provides frequent repetition of vocabulary and structures in context that supports learning.

Mirror talk and self-talk strategies involve narrating what you're doing and what the child is doing. "Mommy is making lunch. I'm cutting the tomato. Red tomato! You're playing with blocks. You're stacking them so high!" This provides rich language input naturally embedding vocabulary and grammar in meaningful contexts. Doing this in both languages at appropriate times provides double benefit.

Labeling objects and actions explicitly teaches vocabulary while building understanding of the symbolic nature of language. Point to objects and name them: "That's a chair. Chair. Silla. You sit on the chair." Action words are equally important: "You're running! Running fast! Corriendo!"

Interactive reading in both languages represents one of the most powerful language development activities. Read books regularly in each language, pointing to pictures, asking questions, letting children turn pages and "read" to you, and talking about stories. Quality children's literature provides rich vocabulary, grammatical structures, and narrative patterns that support all aspects of language development.

Research consistently shows that children with more books at home and more reading experiences show stronger language and literacy development. For bilingual families, having books in both languages and reading regularly in each creates crucial language exposure while building preliteracy skills.

Singing songs and nursery rhymes in both languages supports language learning through rhythm, repetition, and melody that make language patterns memorable. Traditional children's songs in each language provide cultural connections while teaching vocabulary and grammatical structures naturally.

Play-based language learning happens when adults engage in pretend play, building with blocks, playing with toys, or engaging in any play activities while talking with children about what's happening. Play provides contexts for language use that feel meaningful and engaging rather than instructional.

Screen time considerations: While excessive screen time can negatively impact language development, thoughtfully chosen programming in each language can supplement (not replace) human interaction. Programs designed for young children in the target language, watched together with adult discussion, can provide additional language exposure. However, live interaction remains far more important than screen-based input for language development.

Consistency matters more than perfection. Parents shouldn't agonize over every interaction or feel they must maintain rigid language separation in all contexts. What matters is that children receive rich, consistent exposure to both languages through warm, engaging interaction with responsive adults. Natural conversation where adults actually talk with children, not at them, provides the foundation all these strategies rest upon.

One of the most common pieces of advice parents receive—often from well-meaning pediatricians, relatives, or educators unfamiliar with bilingual development research—is to "wait until they master English before introducing another language." This advice, while intuitively appealing, contradicts scientific evidence and can actually reduce language learning outcomes.

The scientific answer is definitively: No, parents should not delay introducing second languages. Research across linguistics, neuroscience, and developmental psychology consistently demonstrates that early childhood represents the optimal period for language acquisition, and that introducing multiple languages simultaneously doesn't harm development while providing substantial advantages.

The critical period for language acquisition refers to early childhood when the brain shows maximum plasticity for language learning. Research from MIT's cognitive science department demonstrates that children can achieve native-like proficiency in languages they're exposed to before age seven much more easily than languages learned later. The neurological systems supporting language become increasingly specialized as children develop, making early language learning more efficient and natural than later learning.

While humans can certainly learn languages throughout life, the ease, naturalness, and ultimate proficiency achievable through early exposure cannot be fully replicated with later learning. A child exposed to Spanish and English from birth can achieve native proficiency in both with appropriate exposure. The same child who hears only English until age six and then begins Spanish will almost certainly speak Spanish with an accent, may struggle with some grammatical subtleties, and will require formal instruction rather than natural acquisition.

Waiting actually reduces natural acquisition capacity by allowing the critical period advantages to pass unused. The window where children learn languages effortlessly, through exposure and interaction rather than formal instruction, is finite. Delaying multilingual exposure means missing the optimal developmental moment when language learning happens most naturally and efficiently.

There's no evidence that waiting helps, substantial evidence it harms outcomes. Research comparing children introduced to bilingualism from birth versus those who began learning second languages later consistently shows that earlier introduction produces better outcomes. Waiting doesn't make English acquisition easier or faster—children exposed to English only develop English at the same rate as bilingual children develop total language capacity. But the bilingual children end up speaking two languages while the English-only children speak one.

The anxiety about "mastering" the first language reflects misunderstanding about how language development works. Languages aren't mastered in early childhood—they continue developing throughout childhood and adolescence. Five-year-old monolinguals haven't "mastered" English; they're still developing vocabulary, grammatical sophistication, and narrative abilities. Similarly, bilingual five-year-olds haven't mastered two languages, but they're developing typically in both.

Practical realities of delayed introduction make it harder to achieve bilingualism. Once children enter school with monolingual peers and English-dominant environments, their motivation and opportunity to learn home languages decrease. The six-year-old entering kindergarten has strong English and potentially weak or absent home language. Starting the home language at this point requires formal lessons, creating negative associations, and competing with English that's now clearly more useful for peer interaction and academic success. This is much harder than natural acquisition from birth.

For families where true simultaneous bilingualism isn't feasible—perhaps because only one parent speaks the minority language and not fluently, or because no daily speakers of the language are available—sequential bilingualism beginning around ages 3-5 can still produce positive outcomes. But this should involve introducing the second language as early as feasible, not waiting until first language is "complete."

The recommendation to delay often reflects confusion between bilingualism causing delay (which it doesn't) and the fact that some bilingual children show delays for unrelated reasons. When a bilingual child has language delay, the appropriate response is evaluation and intervention in both languages, not eliminating one language. Restricting to one language doesn't treat the underlying problem and may complicate treatment by removing context and communication tools.

Professional understanding of bilingual development has evolved significantly, though parents may still encounter outdated attitudes and advice requiring navigation.

Modern best practice in speech-language pathology recognizes bilingualism as an asset to protect and support rather than a complication to eliminate. ASHA's position, reflected in current training standards, is that speech-language pathologists should:

However, not all practicing clinicians have updated training or perspectives, particularly professionals trained before current research became widely known. Parents may encounter speech-language pathologists who recommend using only English at home, suggest that bilingualism is causing delays, or propose restricting to one language until speech problems resolve. These recommendations contradict current evidence-based practice.

If a speech-language pathologist recommends restricting languages, parents should:

Evidence-based speech therapy with bilingual children maintains both languages throughout intervention. A bilingual child with articulation problems receives therapy addressing those sounds in both languages. A bilingual child with language delay receives intervention supporting language development broadly, with activities and strategies applicable across both languages.

Therapy might occur primarily in English for practical reasons (more English-speaking clinicians available, school-based services typically in English), but parents should continue home language exposure at home, and goals should address total communication competence, not just English proficiency.

Educational settings show similar variation in understanding of bilingual development. Progressive preschools and elementary schools recognize bilingualism as strength and work to support both languages. They understand that code-switching is normal, that bilingual children may need extra processing time when working in their less-dominant language, and that assessment should consider cumulative abilities.

Other educational settings, particularly those with limited diversity or traditional monolingual orientations, may view bilingualism as complication. Teachers might express concern about language mixing, recommend that families speak only English at home to help with school readiness, or misinterpret typical bilingual patterns as learning difficulties.

Parents can advocate effectively by:

Questions to ask schools about bilingual support:

The goal is ensuring that educational and therapeutic services support rather than undermine family language goals, recognizing bilingualism as valuable capability deserving protection and promotion.

Real family experiences illustrate how bilingual development unfolds and how concerns resolve—or don't resolve—with appropriate understanding and intervention.

Case Study A: Slow Start, Strong Finish

The Chen family speaks Mandarin at home while living in suburban California. Their daughter Lily seemed slow to talk—by 20 months, she had maybe 10 words total across both languages. At her two-year checkup, the pediatrician expressed concern and suggested the family switch to English only to help Lily catch up.

The Chens, uncomfortable abandoning Mandarin but worried about delay, consulted a bilingual speech-language pathologist for second opinion. Assessment showed that Lily understood vocabulary in both languages appropriate for her age and was attempting communication through gestures and sounds even if clear words were limited. She showed no other developmental concerns and was socially engaged and playful.

The SLP recommended increasing language-rich interaction in both languages—more conversation, reading, singing—and reassessment in six months. The Chens increased focused interaction time, particularly reading books in both languages daily and narrating activities throughout the day.

By 30 months, Lily's language exploded. She was combining words in both languages, her total vocabulary exceeded 200 words, and she was enthusiastically communicating about everything. By age four, she was telling elaborate stories in both languages, though still mixing them freely. By kindergarten, she could separate languages when context required and was beginning to read in English while maintaining strong Mandarin comprehension.

At age eight, Lily is now an advanced reader in English, can read simple texts in Chinese, speaks both languages fluently, and shows the executive function advantages research predicts from bilingualism. The slow start reflected individual variation in language onset, not bilingual confusion or true delay.

Case Study B: True Delay Identified and Treated Bilingually

The Rodriguez-O'Neill family raises their son Miguel bilingually (Spanish and English). By age three, Miguel had very limited language in both—maybe 20 words total and no two-word combinations. He showed difficulty understanding directions in either language, struggled to communicate needs even with gestures, and was becoming increasingly frustrated.

Evaluation by a speech-language pathologist specializing in bilingual children revealed genuine language delay affecting both languages. Miguel wasn't just showing distributed vocabulary across languages—he had significantly limited total language capacity. Additional assessment revealed mild receptive and expressive language delays.

The SLP designed intervention that explicitly maintained both languages. Therapy sessions in English addressed vocabulary, sentence structure, and comprehension, while parents received strategies for supporting the same goals in Spanish at home. The message was clear: Miguel's bilingualism wasn't causing his delay, and restricting to one language wouldn't help—he needed intervention in both languages to support overall communication development.

With two years of speech therapy and family implementation of language-supporting strategies at home, Miguel's language improved dramatically. By kindergarten entry, he had age-appropriate language skills in both languages, though Spanish remained slightly stronger as the primary home language. His bilingualism was preserved while his underlying language difficulties were successfully treated.

The key was recognizing that delay appeared across both languages, not just in one, indicating true language disorder rather than typical bilingual variation requiring intervention rather than just patience.

Case Study C: Lost Language from Pausing Bilingualism

The Patel family spoke Gujarati at home with their daughter Priya until age three, when preschool teachers expressed concern about her English and suggested the family switch to English at home to support school readiness. Anxious about their daughter succeeding, the parents attempted to speak only English at home despite their own limited English proficiency.

Priya's English did improve with preschool exposure, but her Gujarati comprehension plateaued and her production decreased. By kindergarten, she understood but wouldn't speak Gujarati, responding to grandparents in English even when they spoke Gujarati to her. The warm, natural parent-child communication in Gujarati was replaced by stilted, limited English interaction where parents struggled to express themselves clearly.

When Priya was seven, the family consulted a bilingual education specialist about reclaiming Gujarati. The specialist explained that receptive Gujarati could be reactivated but would require substantial intentional effort now—Gujarati enrichment classes, trips to India if possible, motivated practice—that would have been unnecessary had bilingualism been maintained from birth.

The family has been working to rebuild Priya's Gujarati, but it's now formal language learning rather than natural acquisition, requiring time, money, and motivation that might have gone toward other enrichment. Additionally, the years of limited English proficiency at home meant reduced quality of parent-child communication during critical early childhood years.

The Patels wish they'd understood that maintaining Gujarati while Priya naturally acquired English through school was possible and optimal, rather than feeling forced to choose one language over the other based on misconceptions about bilingual development.

When seeking professional guidance about bilingual development, asking informed questions ensures you receive evidence-based recommendations aligned with current research.

"Does my child show delay in both languages?"

This is the critical diagnostic question. If a child is significantly behind in one language but age-appropriate in the other, that reflects exposure differences, not true delay. If significantly behind in both after accounting for exposure patterns, evaluation is appropriate. True language delay crosses both languages; language difference doesn't.

"Is vocabulary developing cumulatively across both languages?"

This question helps professionals recognize bilingual development patterns. A child with 40 words in English and 35 in Spanish has 75 words total—age-appropriate for a two-year-old. Assessing only English vocabulary of 40 words would incorrectly suggest delay. Pushing professionals to consider cumulative vocabulary prevents false diagnoses of delay.

"What strategies support language development in bilingual households without restricting languages?"

This question invites professionals to provide bilingual-supportive strategies rather than defaulting to elimination recommendations. Quality speech-language pathologists and educators will have strategies for rich language exposure, responsive interaction, and support in both languages. If professionals can't provide these strategies and instead recommend monolingual approaches, seek providers with better bilingual expertise.

"How can speech therapy goals be addressed in both languages?"

If your child needs therapy, this question establishes expectation that intervention will support bilingual development rather than focusing exclusively on English. Therapy goals—whether improving articulation, expanding vocabulary, developing grammar, or supporting social communication—can and should be addressed across both languages.

"Are there assessment tools that properly evaluate bilingual children?"

Many standardized tests are normed only on monolingual English speakers, making them inappropriate for bilingual children. Asking about assessment approaches demonstrates that you understand this limitation. Comprehensive bilingual evaluation might involve testing in both languages, parent interviews about language use patterns, observation in different contexts, and dynamic assessment examining learning potential rather than just current performance.

"What research supports your recommendation?"

If a professional recommends restricting to one language or claims bilingualism causes delays, asking for supporting research invites them to reconsider. Current research doesn't support these recommendations, and professionals making them often rely on outdated training or personal assumptions rather than evidence. This question—asked respectfully—can prompt helpful reconsideration.

"Can you refer us to a specialist in bilingual child development?"

If current providers aren't knowledgeable about bilingual development, requesting specialist referral is appropriate. Not all communities have bilingual specialists, but larger cities and university settings often have clinicians and researchers with specific expertise in multilingual development.

"What signs would indicate my child needs evaluation versus just typical bilingual variation?"

This question invites professionals to distinguish concerning patterns from normal bilingual development, ensuring you know what warrants attention versus what's expected variation. The red flags discussed earlier should guide these conversations.

"How can we maintain the home language while supporting English development?"

This question explicitly frames bilingualism as a goal to support rather than problem to solve, inviting collaborative problem-solving about how to support both languages effectively. It shifts conversation from either/or to both/and approaches.

The key is approaching professionals as partners who should understand bilingual development and support family language goals. When professionals lack this understanding or make recommendations contradicting research, parents need confidence to seek second opinions, request different approaches, and advocate for evidence-based practices that honor bilingualism while addressing any genuine developmental concerns.

Sofia's mother from the introduction can take a deep breath. Her daughter, mixing Spanish and English with a limited vocabulary at 20 months, is developing exactly as bilingual toddlers should. She isn't confused. She isn't delayed. She's building dual language systems that will serve her throughout life while strengthening the executive function, cognitive flexibility, and metalinguistic awareness that research shows are bilingualism's extraordinary gifts.

The fear that drives so many bilingual parents to doubt their language choices reflects widespread myths that contradict scientific evidence. Bilingualism doesn't delay speech development. It doesn't confuse children. It doesn't create learning difficulties or academic disadvantages. What it does do is provide cognitive advantages, cultural connections, and communication capabilities that monolingual development cannot match.

When bilingual children seem slow to speak, the explanation is almost never that two languages are too much. It's that vocabulary is distributed across languages, making each individual language seem smaller when it's really part of a larger whole. It's that code-switching is mistaken for confusion when it's actually sophistication. It's that typical variation in language onset is misinterpreted through monolingual lenses that don't account for bilingual patterns.

The rare times when bilingual children do have speech or language delays, the delays are caused by the same factors that affect monolingual children—underlying language disorders, hearing loss, developmental conditions—and those delays appear across both languages, not just one. When true delays exist, the solution is intervention addressing the actual problem while maintaining both languages, not abandoning bilingualism based on false assumption that language exposure caused the difficulty.

Your role as parent of a bilingual child is to:

Two languages are not a burden on developing minds. They're a bridge—to cognitive advantages that support learning across domains, to cultural identity and family connections that ground children in rich heritage, to communication capabilities opening opportunities throughout life, and to ways of thinking that transcend what single languages can express.

Related posts

Discover why play is not the opposite of learning but the most powerful driver of cognitive, social, and emotional development in early childhood.

Discover how left-handed children experience learning differently, why handwriting and classroom tools can create unnecessary frustration, and which simple accommodations turn daily struggles into confidence.

Worried your 4-year-old still can’t name letters? Learn what’s truly normal for letter recognition, when to relax, when to seek help, and how to gently support learning.

Learn how to recognize a highly sensitive preschooler, avoid misdiagnosis, and adapt nursery and home environments so your child feels safe, understood, and able to thrive.

Worried your toddler isn’t talking yet? This guide explains the difference between “late talker” and speech delay, key red flags, when to seek an evaluation, and how to support language at home.