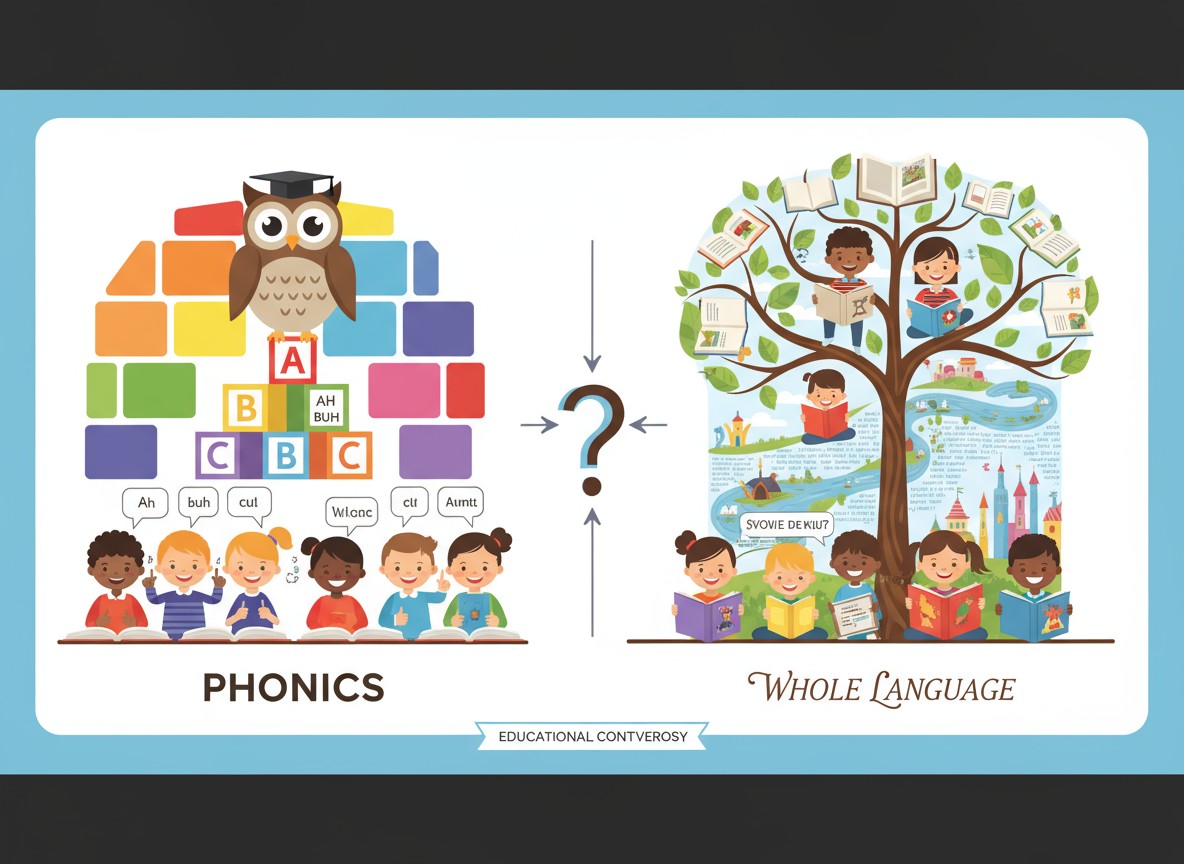

The reading instruction controversy represents one of education’s most heated battles, with profound implications for your child’s academic trajectory that extend far beyond simply learning to decode words on a page. Schools choose between phonics-oriented programs that explicitly train children to connect written symbols with spoken sounds versus meaning-focused methods that treat reading as something children naturally absorb through exposure to books and stories. This choice shapes whether your child develops the core abilities needed for lifelong literacy or faces ongoing reading challenges that cascade into every subject area. The frustration for parents comes from having limited influence over school curriculum decisions despite being ultimately accountable for their child’s educational outcomes—you cannot dictate which teaching framework your child’s teacher implements, yet reading proficiency will determine academic opportunities, career pathways, and personal confidence throughout their lifetime.

The challenge grows more complex because advocates on both sides reference supporting research, skilled educators achieve results using divergent philosophies, and the specialized terminology obscures fundamental differences in how various programs conceptualize the reading process. Phonics supporters point to cognitive neuroscience demonstrating that teaching letter-sound connections systematically yields better outcomes, especially for children who struggle, while meaning-emphasis proponents contend that reading involves constructing understanding rather than merely sounding out letters, arguing that phonics drills feel mechanical and disconnect reading from its real purpose of comprehension. Adding to the confusion, numerous schools describe their curriculum as “balanced literacy” that supposedly integrates both philosophies—yet this label masks enormous variation, with some schools delivering solid phonics alongside rich reading experiences while others offer token phonics within predominantly meaning-focused instruction. Understanding which approach your child actually receives demands recognizing the distinguishing features of each method, identifying them in actual teaching practices, and assessing whether your child’s instruction reflects the research consensus on effective literacy development.

This thorough examination tackles the essential question of identifying your school’s reading philosophy and determining whether it delivers the instruction your child requires to become a proficient reader. The discussion illuminates what phonics and meaning-focused approaches actually entail in classroom settings, methods for recognizing which philosophy guides your child’s instruction through concrete observable markers, what research from reading psychology and cognitive science reveals about teaching methods that produce strong readers, reasons the instructional debates persist despite research evidence, how balanced programs vary dramatically in quality and substance, techniques for strengthening inadequate school instruction through home support, constructive advocacy strategies for improving school reading programs, red flags indicating your child lacks sufficient phonics teaching, and criteria for determining when professional intervention becomes essential. The analysis draws from literacy research documenting how skilled readers process written language, comparative studies tracking long-term outcomes from different teaching methods, expert guidance from reading organizations, classroom documentation showing what happens during literacy instruction, and accounts from parents who successfully navigated these educational controversies. Crucially, this analysis emphasizes that comprehending your school’s instructional philosophy enables you to guarantee your child acquires critical foundational abilities—through advocating for improved school teaching, supplementing at home, or pursuing intervention when problems surface—rather than discovering years later that insufficient early reading instruction created avoidable learning obstacles.

Recognizing phonics teaching: Classroom characteristics and practices

Phonics programs train children in the predictable connections between written letters and spoken sounds, allowing them to unlock unfamiliar words by separating them into sound units and combining those sounds into words. Quality phonics curricula follow organized progressions introducing letter-sound relationships incrementally—commonly beginning with individual consonants and short vowels, then moving toward consonant combinations, paired letters making single sounds, long vowel patterns, and sophisticated spelling structures. Children learn explicitly that the letter “m” produces the sound heard at the start of “mom,” that “ch” together creates one distinct sound, and that the pattern “oa” consistently makes the long “o” sound in words like “boat” and “road.” Teaching focuses on direct instruction rather than expecting children to discover these relationships through reading exposure—teachers explicitly demonstrate patterns, model decoding techniques, offer guided practice with immediate correction, and systematically revisit previously taught concepts while introducing additional ones.

In classrooms using phonics, you witness dedicated daily lessons specifically addressing letter-sound relationships where teachers show how to break words into separate sounds, how to merge sounds together forming words, and how to transfer these abilities to reading continuous text. Children work with specially designed decodable books featuring vocabulary controlled to use letter patterns already taught, permitting them to successfully implement their phonics knowledge rather than encountering numerous words requiring sight memorization. Spelling lessons connect directly to phonics teaching—children learn to translate sounds into written symbols using identical patterns they’re mastering for reading, strengthening the reciprocal connection between reading and writing. Testing emphasizes whether children can decode invented nonsense words never previously encountered, proving mastery of alphabetic principles rather than mere word memorization. The philosophy recognizes that English spelling demonstrates predictable patterns despite apparent irregularities, and that directly teaching these patterns equips children with tools for independently decoding most written words they encounter.

Recognizing meaning-focused teaching: Classroom characteristics and practices

Meaning-focused methods emphasize that reading primarily involves deriving meaning from text rather than decoding individual words, positioning reading as an organic process children develop through literature exposure and purposeful reading experiences rather than through structured skill teaching. This educational philosophy views reading similarly to spoken language acquisition—just as children master speaking without formal grammar instruction by immersing themselves in oral communication, this theory proposes children learn reading by immersing themselves in quality literature and using surrounding context, illustrations, and overall story understanding to determine unfamiliar words. Teachers implementing this philosophy minimize systematic phonics teaching, instead encouraging children to anticipate words using context, employ beginning letters as one of several clues, examine pictures for hints, and verify whether their reading “makes sense” and “sounds natural” rather than methodically processing every letter in unrecognized words.

In meaning-focused classrooms, you observe substantial time devoted to reading authentic literature rather than practicing with phonics materials or controlled-vocabulary texts, with teachers reading aloud to students, children reading independently or collaboratively, and conversations emphasizing story understanding and personal text connections. Children master frequently-used words through repeated encounters and memorization—common words like “the,” “said,” and “was” taught as complete units rather than through letter-sound analysis. When children meet unfamiliar words while reading, teachers prompt them to “examine the illustration,” “consider what makes sense,” or “continue reading and return to it” rather than systematically sounding it out letter by letter. Writing instruction emphasizes freely expressing ideas through phonetic spelling rather than conventional spelling patterns, believing children will gradually approximate standard spelling through reading exposure. Assessment emphasizes whether children comprehend and engage with text meaningfully, whether they demonstrate reading enthusiasm, and whether they self-correct based on meaning rather than specifically measuring decoding precision. The philosophy reflects beliefs that reading for understanding represents genuine literacy while isolated phonics exercises feel artificial and potentially harm children’s reading motivation.

What literacy research demonstrates: The evidence foundation for effective teaching

Decades of investigation using brain imaging technology, controlled comparisons of teaching approaches, and longitudinal monitoring of reading development have produced clear scientific agreement about how children learn reading most successfully. The evidence strongly supports structured explicit phonics teaching as the foundation for literacy development, with comprehensive research reviews from the National Reading Panel and numerous meta-analyses showing that phonics teaching produces substantially superior reading results than meaning-focused methods, particularly for children vulnerable to reading challenges. Brain imaging investigations reveal that proficient readers automatically process letter-sound connections when reading—they don’t bypass phonological processing by jumping straight from word shapes to meaning, as meaning-focused theory suggests, but rather the phonological pathway becomes highly efficient with practice that it feels automatic and immediate to skilled readers.

Investigation demonstrates that children don’t spontaneously discover letter-sound relationships through reading exposure independently—while some children deduce these patterns without explicit teaching, most require direct instruction that methodically teaches alphabetic principles. Research comparing classrooms using divergent approaches consistently finds that structured phonics teaching produces superior word reading accuracy, superior reading fluency, superior spelling, and equivalent or superior reading comprehension than meaning-focused methods, with especially striking advantages for struggling readers, children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and children with language-based learning challenges. Reading science has documented that skilled reading demands automatic word recognition built on efficient phonological processing—when children struggle to decode words accurately and quickly, their mental resources get consumed by word-level processing rather than being available for comprehension, whereas children with strong decoding abilities can focus attention on understanding and analyzing text meaning. Importantly, investigation shows that phonics teaching doesn’t harm reading enthusiasm or comprehension when delivered effectively—children taught structured phonics develop equivalent enthusiasm for reading and superior comprehension compared to meaning-focused students by third grade, once their stronger decoding abilities enable them to independently read increasingly complex texts.

Determining your school’s teaching philosophy: Observable markers

Establishing which reading philosophy your child’s school implements requires examining beyond which curriculum materials teachers mention and observing actual classroom activities and resources. Visit your child’s classroom during literacy block if possible, examining which activities fill daily reading time and what teachers emphasize during lessons. Examine the books your child carries home for practice—controlled-vocabulary books featuring words using phonics patterns previously taught indicate phonics emphasis, while leveled readers featuring high-frequency words, repetitive patterns, and picture support suggest meaning-focused approaches. Review homework and classwork papers for evidence of phonics skill development—worksheets or activities emphasizing letter sounds, blending, segmenting, and spelling patterns indicate phonics priority, while assignments requesting children write about books they’ve read or illustrate story responses without specific phonics practice suggest meaning-focused approaches.

Ask your child’s teacher targeted questions revealing their instructional beliefs and methods: How do you teach children to tackle unfamiliar words during reading? What phonics progression or framework do you implement? How much daily time is allocated to explicit phonics teaching versus independent reading? Do you utilize controlled-vocabulary texts or leveled readers during guided reading? How do you teach spelling—through phonics patterns or through word memorization? Teachers implementing structured phonics can describe their phonics progression clearly, explain how they teach specific letter-sound relationships methodically, and describe how they verify children master each stage before progressing. Teachers using meaning-focused approaches typically describe helping children employ “multiple information sources” including meaning, grammar, and visual information, discuss developing reading through authentic literature experiences, and may express concerns that excessive phonics teaching damages reading enthusiasm. Investigate whether your school adopts specific commercial reading curricula—programs like Wilson Reading, Orton-Gillingham, or Fundations indicate structured phonics approaches, while programs like Teachers College Reading and Writing Workshop or Fountas & Pinnell Leveled Literacy Intervention suggest balanced literacy with potentially insufficient phonics depending on implementation.

The balanced literacy puzzle: What it signifies in actual classrooms

Numerous schools characterize their reading approach as “balanced literacy,” purporting to combine both phonics and meaning-focused elements, yet this descriptor signifies vastly different things in different contexts making it essentially meaningless without examining actual implementation. In optimal scenarios, balanced literacy signifies structured explicit phonics teaching as the foundation augmented by rich reading experiences with quality literature, guided reading lessons supporting comprehension strategies, independent reading time developing fluency and engagement, and writing instruction connecting to phonics learning. This genuinely balanced approach aligns with reading science recommendations emphasizing that while phonics provides critical foundational abilities, children also need extensive opportunities to read connected text, develop comprehension strategies, build vocabulary through wide reading, and experience reading as meaningful and enjoyable rather than merely completing skill exercises.

However, in numerous schools claiming balanced literacy, the descriptor actually characterizes predominantly meaning-focused teaching with minimal phonics added—perhaps ten minutes daily of letter-sound teaching embedded within an hour-long literacy block dominated by meaning-focused activities, or phonics teaching lacking systematic progression and structure, or programs teaching students to employ letter sounds as merely one of several cueing strategies rather than as the primary tool for word identification. Investigation of balanced literacy implementation reveals tremendous variability, with the approach’s effectiveness depending entirely on whether phonics teaching is genuinely systematic, explicit, and substantial rather than incidental or minimal. Pose pointed questions about the phonics component specifically—how many daily minutes, what progression and structure, whether it’s explicit direct teaching or merely mentioned during shared reading, and how teachers verify whether children have mastered phonics concepts before advancing. Don’t accept vague assurances that the program is “balanced” without investigating what that balance actually entails regarding time allocation and teaching practices.

Red flags suggesting insufficient phonics teaching

Multiple markers suggest your child may not be receiving the structured phonics teaching they need to develop strong literacy abilities. Your child can read books they’ve practiced repeatedly but cannot decode unfamiliar words containing similar phonics patterns—for instance, they read “dog” successfully in their practice book but cannot read “log” or “fog” independently when those words appear in different contexts. They depend heavily on memorizing words visually and using context or pictures to guess at words rather than methodically processing them sound by sound. When attempting to read unfamiliar words, they guess based on initial letters rather than processing all letter-sounds sequentially—reading “happy” as “home” because both start with “h,” or reading “black” as “blue” because the beginning looks similar. They spell words in ways suggesting they’re guessing at letters rather than encoding sounds methodically—writing “jragun” for “dragon” or “wut” for “want,” indicating they haven’t learned the spelling patterns representing these sounds.

Your child’s reading development plateaus after initial success with simple books featuring high-frequency words and picture support—they manage easy books with repetitive text but struggle substantially when advancing to books requiring decoding more sophisticated words. They cannot break words into individual sounds or merge sounds together to form words when you practice these abilities at home, suggesting phonological awareness and phonics abilities haven’t developed sufficiently. Reading homework and school assignments don’t include regular phonics practice or controlled-vocabulary texts aligned with specific phonics patterns, instead featuring leveled readers with numerous words your child must memorize rather than decode. By second grade, your child reads slowly and laboriously word-by-word rather than developing reading fluency, or they read quickly but with numerous errors skipping or substituting words based on meaning rather than actually decoding the words on the page. These red flags don’t necessarily indicate your child has a learning disability—they may simply indicate that the reading teaching they’re receiving doesn’t provide the structured phonics foundation most children require to become proficient readers.

Strengthening inadequate school teaching through home support

If your child’s school uses predominantly meaning-focused methods or provides insufficient phonics teaching, you can supplement at home to guarantee they develop essential decoding abilities, though this demands consistent time investment and appropriate resources. Invest in a structured phonics program designed for home implementation—options include programs like All About Reading, Logic of English, or phonics applications like Reading Eggs that provide organized sequential teaching. Dedicate fifteen to twenty daily minutes to explicit phonics work separate from your child’s regular homework, treating it as essential skill development rather than optional enrichment. Follow the program’s progression methodically rather than jumping around, guaranteeing your child masters each stage before advancing to more sophisticated patterns.

Practice phonological awareness activities that build the underlying sound awareness necessary for phonics learning—engage in rhyming games, practice clapping syllables in words, break words into individual sounds, and practice merging sounds together to form words. Utilize controlled-vocabulary books for reading practice rather than depending only on books your child brings home from school—these specially designed texts feature controlled vocabulary using phonics patterns your child has mastered, enabling them to practice implementing phonics abilities successfully rather than guessing at words. Make the practice engaging rather than tedious by incorporating multisensory activities like writing letters in sand, constructing words with magnetic letters, or playing phonics games rather than merely completing worksheets. Maintain this supplemental work consistently over months rather than stopping after several weeks—phonics abilities develop gradually with repeated practice and application. However, recognize your limitations as a parent-teacher, particularly if your child demonstrates signs of significant reading challenges beyond just inadequate teaching—if your child struggles despite consistent home phonics practice, or if the home teaching creates excessive frustration and conflict, consider professional reading intervention rather than continuing ineffective parent-led instruction.

Advocating for improved school reading teaching

Parents can advocate for better literacy teaching at their child’s school, though changing established instructional practices demands strategic, persistent effort. Begin by requesting a meeting with your child’s teacher sharing specific observations about your child’s literacy development and asking detailed questions about the phonics teaching provided. Present your concerns using reading science research language rather than merely parent intuition—reference recommendations from organizations like the International Dyslexia Association or Reading League, cite research agreement about effective literacy teaching, and ask how the school’s approach aligns with evidence-based practices. Request specific accommodations for your child if the school won’t modify its overall approach—asking that they receive supplemental phonics teaching through reading intervention services, requesting they work with the reading specialist for structured phonics teaching even if they haven’t been formally identified as struggling readers yet, or asking for controlled-vocabulary books to supplement the leveled readers used in guided reading.

Connect with other parents sharing concerns about literacy teaching, presenting yourselves as a group concerned about literacy outcomes rather than as individual complainers. Attend school board meetings when literacy curriculum is discussed, bringing research articles and expert recommendations about effective literacy teaching. Reference state literacy policies or legislation requiring phonics teaching if your state has enacted reading science-based requirements, pointing out discrepancies between state requirements and actual school practices. Understand that teachers often use meaning-focused approaches because that’s what their training emphasized and what their school requires rather than personal preference—approach conversations collaboratively rather than accusatorily, positioning yourself as pursuing what’s best for all students rather than attacking teachers personally. Be prepared for resistance, particularly from administrators and literacy coaches invested in current programs, but persist patiently knowing that numerous districts nationwide have shifted toward phonics-based teaching in response to parent advocacy and reading science evidence. Document your conversations and your child’s literacy development carefully, creating a paper trail if you eventually need to request formal intervention services or justify a school transfer based on inadequate literacy teaching.

Hope and encouragement: Your engagement makes the difference

Reading challenges caused by inadequate teaching are highly treatable with appropriate intervention, unlike inherent learning disabilities

Many struggling readers advance to grade level within one to two years when they receive structured phonics teaching

Parent awareness of literacy teaching quality protects children from years of reading struggles before problems are identified

More school districts adopt evidence-based literacy practices each year as reading science awareness increases

Children receiving supplemental phonics at home while attending meaning-focused schools can still develop strong literacy abilities

Your advocacy for better literacy teaching potentially helps not just your child but all students in your school

Early attention to literacy teaching quality prevents the need for intensive intervention later when reading problems compound over time

When professional intervention becomes essential

Sometimes children need professional reading intervention beyond what parents can deliver through home supplementation, particularly if reading challenges persist despite adequate phonics teaching or if children demonstrate signs of dyslexia or other language-based learning challenges. Request formal reading evaluation through your school’s special education system if your child is substantially behind reading benchmarks, if their literacy abilities regress rather than progressing, if they’ve received intervention services without meaningful improvement, or if they exhibit severe reading struggles affecting their emotional wellbeing and school confidence. The evaluation should include comprehensive assessment of phonological awareness, phonics abilities, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and spelling rather than merely informal reading level assessments.

Consider private reading tutoring with specialists trained in structured literacy approaches like Orton-Gillingham, Wilson Reading, or Barton Reading if school intervention proves insufficient or if wait times for school services are excessive while your child continues falling further behind. Quality reading intervention demands specialized training beyond general tutoring—look for professionals with credentials from organizations like the Academy of Orton-Gillingham Practitioners and Educators or the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education rather than general tutors without specialized reading training. Intensive intervention providing structured explicit phonics teaching through qualified specialists can remediate reading challenges even for children who’ve experienced years of ineffective teaching, though earlier intervention produces better outcomes with less intensive services required. Don’t delay pursuing professional help hoping your child will catch up independently or waiting to see if they mature into reading—investigation clearly demonstrates that children who struggle with reading in first grade rarely catch up without explicit intervention, and the gap between struggling readers and their peers widens over time without appropriate support.

Discovering that your child’s school may be implementing literacy teaching methods not aligned with research evidence feels overwhelming and frightening—you’ve trusted their educators and education system to deliver the instruction your child requires, only to learn that pedagogical debates and educational philosophies may be placing your child at risk for reading challenges that could have been prevented with different approaches. The frustration intensifies knowing that literacy teaching methods represent school-level decisions largely outside individual parent control, yet reading success affects virtually every dimension of your child’s academic future and overall wellbeing. However, comprehending the distinctions between phonics and meaning-focused approaches, recognizing what your school actually implements versus what they claim, and knowing red flags of inadequate teaching empowers you to protect your child’s literacy development through advocacy, supplementation, or intervention rather than passively hoping everything works out while problems potentially compound. The evidence from decades of literacy investigation is clear and consistent—structured explicit phonics teaching provides the foundation virtually all children need to become proficient readers, while meaning-focused approaches leave many children without essential decoding abilities, particularly children who don’t intuitively discover letter-sound relationships independently or who have language-based learning differences. Your awareness of these issues and your willingness to investigate your school’s literacy practices demonstrates exactly the kind of informed parent advocacy that protects children from teaching approaches that may not serve them well. Whether your involvement means requesting specific accommodations within your current school, delivering supplemental phonics teaching at home, advocating for curriculum changes that help all students, or pursuing intervention services for your struggling reader, your informed attention to literacy teaching quality makes an enormous difference in your child’s literacy outcomes. The literacy abilities your child develops during these early elementary years create the foundation for all future learning—students who become strong readers by third grade access increasingly sophisticated content across all subjects, while those who struggle with reading face compounding challenges as academic demands increase. Your efforts now guaranteeing your child receives the structured phonics teaching investigation demonstrates they need, whether through school teaching or supplementation, prevents years of reading struggles and academic frustration that are far more difficult to remediate later than to prevent early. Trust the investigation evidence over educational fads, trust your observations of your child’s actual literacy development over vague reassurances that everything is fine, and trust that your advocacy on behalf of your child’s literacy learning will serve them throughout their entire educational journey and beyond into lives as confident, capable readers who can access any information and engage with any text they encounter. The literacy teaching debates may continue among educators, but the science is settled—phonics teaching works, your awareness matters, and your child’s reading future benefits enormously from your informed attention to this critical dimension of their early education.