Sensory processing differences affect how children’s brains receive, interpret, and respond to information coming through their eight sensory systems—the five everyone knows about including sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch, plus three lesser-known systems involving body position awareness called proprioception, movement and balance called the vestibular sense, and internal body signals called interoception. When these systems function typically, children can automatically filter relevant sensory information from background noise, modulate their responses appropriately to different sensory inputs, and maintain comfortable arousal levels that allow them to focus, learn, and interact socially without becoming overwhelmed or under-stimulated. However, approximately one in twenty children experiences sensory processing challenges significant enough to interfere with daily functioning, though many never receive formal diagnosis or appropriate support because their difficulties get misinterpreted as behavioral problems, defiance, attention-seeking, laziness, or deliberate rule-breaking rather than being recognized as involuntary neurological responses to sensory experiences that feel genuinely distressing, painful, or insufficient to nervous systems wired differently from their peers.

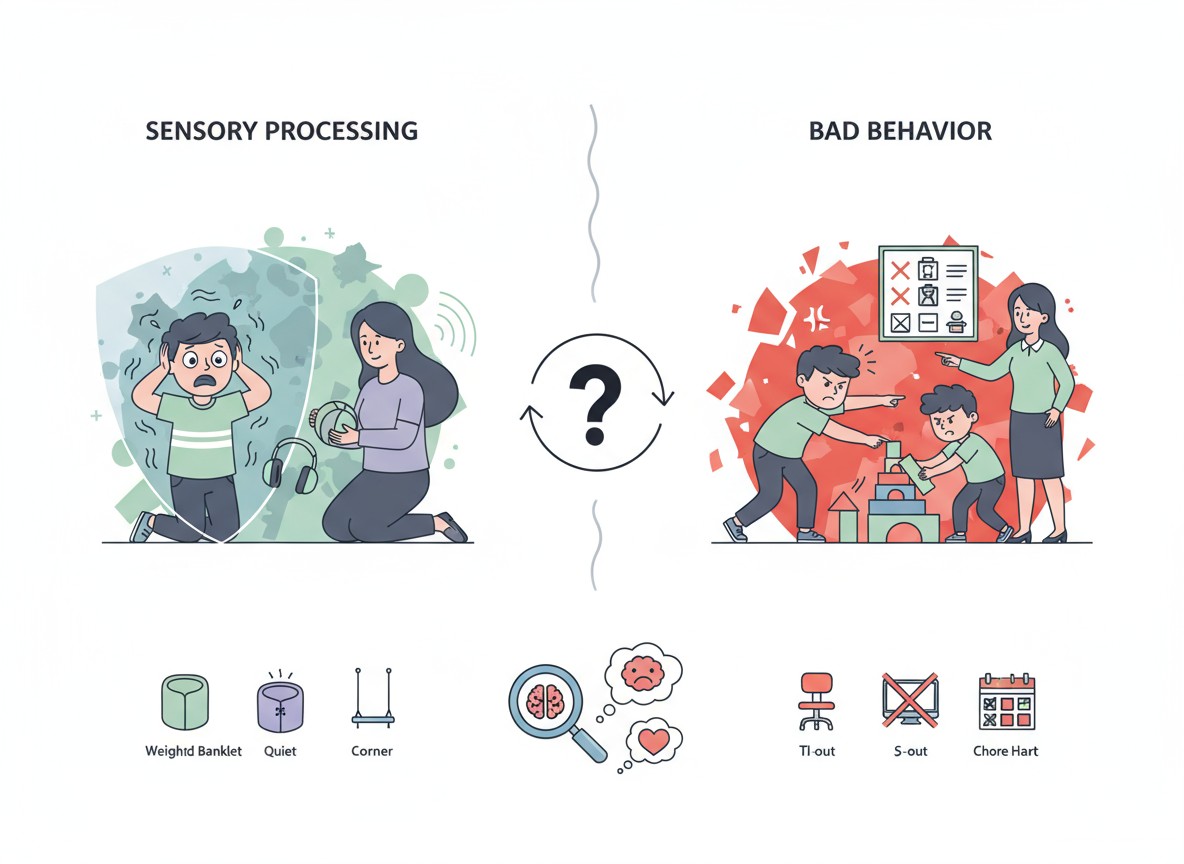

Teachers occupy a unique position to identify sensory processing differences because they observe children across diverse situations throughout extended time periods, noticing patterns that parents might miss when children only struggle in specific environments outside the home or when children expend enormous energy maintaining control at school then collapse into meltdowns once they reach the safety of home where demands feel more manageable. This comprehensive guide helps educators distinguish between behavioral issues stemming from choices children make versus sensory challenges representing involuntary neurological responses children cannot simply decide to control through willpower alone, explaining the critical differences in how these two distinct situations present in classroom settings, why traditional behavior management approaches often backfire spectacularly when applied to sensory difficulties, and most importantly what actually helps children with sensory processing differences succeed academically and socially when appropriate accommodations and environmental modifications replace punitive consequences that worsen rather than improve the underlying difficulties driving concerning behaviors that adults misinterpret as willful misbehavior.

The information presented draws from current research on sensory processing patterns, practical classroom experiences shared by teachers working with neurodivergent students, guidance from occupational therapists specializing in sensory integration, and insights from adults with sensory processing differences who can articulate what childhood sensory experiences felt like from the inside perspective that young children often cannot explain adequately to adults trying to help them. Most critically, this article emphasizes that recognizing sensory processing differences represents not about making excuses for problematic behavior but rather about correctly identifying the root cause of difficulties so appropriate interventions can address actual needs rather than applying ineffective behavioral strategies to neurological challenges that require entirely different support approaches, ultimately helping struggling children succeed rather than continuing cycles of punishment and frustration that damage self-esteem while failing to improve outcomes for anyone involved.

The Fundamental Difference: Involuntary Reactions vs Conscious Choices

The single most important distinction between sensory processing challenges and behavioral issues centers on whether children experience conscious control over their responses to situations or whether their nervous systems react automatically before higher-level thinking processes can intervene to modify behavior. Behavioral problems involve children making choices about how to respond even if those choices stem from inadequate skills, poor emotional regulation, unclear expectations, or learned patterns from past experiences—the critical element being that children possess capacity to make different choices when properly motivated, taught alternative responses, or faced with meaningful consequences that shift their cost-benefit analysis about whether problematic behavior serves their interests. Traditional behavior management approaches work reasonably well for these situations precisely because they target the decision-making process, teaching children that certain choices produce preferred outcomes while other choices result in undesired consequences, gradually shaping behavior through consistent application of logical consequences paired with explicit instruction in more appropriate alternative responses.

Sensory processing challenges operate completely differently because children’s nervous systems react to sensory input automatically through primitive brain regions responsible for survival responses before information reaches cortical areas where conscious decision-making occurs, meaning by the time children become aware they are responding, their bodies have already initiated fight-flight-freeze reactions that feel overwhelming and uncontrollable regardless of how desperately children want to behave appropriately. A child who melts down when entering a loud cafeteria is not choosing to be difficult—their auditory system genuinely experiences that volume level as threatening or painful, triggering automatic stress responses designed to escape perceived danger that feel every bit as compelling as your urge to jump back when you unexpectedly encounter a snake on a hiking trail. Similarly, the child who constantly fidgets and cannot sit still during story time is not deliberately defying expectations but rather seeking movement input their under-responsive vestibular and proprioceptive systems require to maintain alert arousal levels necessary for attention and learning, much like you might unconsciously tap your foot or shift position during a lengthy meeting without any awareness you are moving until someone points it out.

This fundamental difference has enormous implications for intervention approaches because applying behavioral strategies to sensory challenges essentially punishes children for involuntary neurological responses they cannot control, similar to disciplining a student for sneezing during silent reading or for their stomach growling during math—the response happens automatically regardless of rules, consequences, or desire to comply. When teachers implement behavior charts, remove privileges, assign consequences, or express disappointment toward children struggling with sensory processing, those approaches not only fail to improve the situation since children cannot voluntarily stop their nervous system responses, but actually worsen difficulties by adding emotional distress and shame to already overwhelming sensory experiences, potentially damaging trust in adults and self-esteem while teaching children that their bodies are wrong and their distress does not deserve compassion. Conversely, when teachers correctly identify sensory processing as the root cause and implement appropriate environmental modifications, sensory tools, and regulation strategies, children often demonstrate immediate dramatic improvement precisely because interventions address the actual neurological needs driving concerning behaviors rather than attempting to override biology through reward and punishment systems designed for entirely different situations.

Key Behavioral Patterns That Signal Sensory Processing Differences

Several distinctive patterns help teachers recognize when concerning behaviors likely stem from sensory processing challenges rather than behavioral choices requiring different intervention approaches. The first critical pattern involves consistency across similar sensory contexts combined with absence of problems in different contexts—children with sensory processing differences typically struggle predictably in specific situations involving particular sensory triggers while functioning well in environments that do not activate their sensory challenges, whereas children with primary behavioral issues demonstrate more variable patterns depending on factors like supervision level, peer influences, motivation, or mood rather than showing tight connections between specific environmental features and behavioral responses. A child who consistently melts down during transitions to loud chaotic spaces like cafeterias, gymnasiums, or assemblies but participates appropriately during quiet structured classroom activities almost certainly experiences auditory sensory challenges, while a child who misbehaves inconsistently across various settings regardless of sensory characteristics more likely has behavioral issues requiring different support.

The second revealing pattern centers on whether traditional behavior management approaches improve or worsen the situation over time with consistent implementation—behavioral issues typically respond at least somewhat to well-designed behavior plans that provide clear expectations, teach alternative skills, and deliver consistent consequences because these interventions target the decision-making processes underlying chosen behaviors, whereas sensory processing challenges show no improvement or actually deteriorate when subjected to behavioral interventions precisely because such approaches cannot modify involuntary neurological responses and may increase distress through added pressure and consequences that children experience as punishment for something beyond their control. When you have diligently implemented a behavior chart for six weeks with perfect consistency yet see zero progress or notice the child seems increasingly anxious and defeated despite your encouragement, that pattern strongly suggests you are applying behavioral strategies to a sensory processing situation that requires completely different support involving environmental modifications and sensory accommodations rather than behavior change techniques.

The third diagnostic pattern examines whether children demonstrate awareness and remorse about concerning behaviors versus appearing genuinely confused or distressed about their responses in ways suggesting they do not experience control over what happened. Children making behavioral choices typically show signs they understand expectations and recognize when they violate rules even if they choose problematic behavior anyway for various reasons, often demonstrating calculating quality to their actions or showing defiance and indifference toward consequences that suggest conscious decision-making processes at work. In contrast, children struggling with sensory processing frequently express genuine confusion about why they responded as they did, display significant distress during and after sensory meltdowns in ways demonstrating those experiences feel horrible rather than providing any perceived benefit, and often articulate frustration that their bodies “do not listen” or that they “could not help it” despite desperately wanting to meet expectations. When children regularly apologize sincerely after meltdowns, express fear about future situations involving similar sensory triggers, or demonstrate clear motivation to behave appropriately but still struggle in predictable sensory contexts, those patterns indicate neurological challenges overwhelming their best efforts rather than behavioral choices requiring disciplinary responses.

Observable Differences Between Sensory Challenges and Behavioral Issues

Sensory processing challenges typically show: Predictable patterns tied to specific sensory contexts such as particular sounds, textures, visual stimuli, or movement experiences. Children often have good days in low-sensory-demand environments but struggle consistently when sensory load increases regardless of behavioral expectations or consequences in place. Their difficulties appear outside their conscious control and they frequently express distress about their own responses, showing genuine desire to meet expectations but inability to do so when sensory systems become overwhelmed or under-stimulated beyond their current capacity to regulate.

Behavioral issues typically show: More variable patterns influenced by factors beyond sensory environment including who is supervising, what activities interest them, whether peers are watching, what they can gain or avoid through specific behaviors, and their current emotional state or energy level. Children often demonstrate calculating quality to their choices, may show defiance or indifference toward consequences, and generally possess capacity to behave appropriately when motivation is sufficiently high or supervision is particularly attentive, proving they can control responses even if they frequently choose not to in various circumstances.

Important caveat: Some children experience both sensory processing challenges and behavioral issues simultaneously, requiring careful analysis to determine which difficulties stem from each source so appropriate interventions can address sensory needs through accommodation while behavioral concerns receive appropriate consequences and skill-building, recognizing that punishing sensory struggles damages children while failing to address behavioral choices enables concerning patterns to continue without appropriate limits or learning opportunities.

The Three Primary Sensory Processing Patterns Teachers Encounter

Sensory processing challenges manifest through three primary patterns that look quite different in classroom settings but all stem from nervous systems processing sensory information atypically compared to neurotypical peers. The first pattern involves sensory over-responsivity where children’s nervous systems respond more intensely to sensory input than typical, experiencing stimuli as louder, brighter, scratchier, smellier, or more overwhelming than peers do in identical situations, essentially living with all sensory volume dials turned up several notches beyond comfortable levels. These children might cover their ears during routine classroom noise that other students barely notice, refuse to touch materials like paint or glue that feel genuinely intolerable rather than merely messy, become distressed by fluorescent light humming that you cannot even hear, or melt down in cafeterias where combined sensory input from noise, smells, visual chaos, and social demands exceeds their nervous system capacity to process and regulate responses. Teachers often misinterpret sensory over-responsivity as children being overly dramatic, attention-seeking, or manipulative because the triggering stimuli seem innocuous to neurotypical nervous systems, but for these children the distress is absolutely genuine even if adults cannot perceive what makes situations so overwhelming.

The second pattern involves sensory under-responsivity where children’s nervous systems respond less intensely to sensory input than typical, requiring stronger stimulation to register sensations that peers feel easily at normal levels, like trying to hear conversations through thick walls that muffle everything to barely audible levels. These children might seem oblivious to their names being called, appear not to notice when they are bumped or touched, fail to respond to visual cues that work for other students, show decreased awareness of pain or temperature that creates safety concerns, or demonstrate difficulty maintaining alert arousal levels during passive activities because their nervous systems receive insufficient stimulation to support attention and engagement. Teachers often misinterpret sensory under-responsivity as inattention, laziness, defiance, or learning disabilities because these children seem unmotivated or unaware of expectations that appear obvious to everyone else, when actually their nervous systems simply do not register sensory information strongly enough to capture attention or maintain alertness without significant effort or enhanced sensory input beyond what typical classroom environments naturally provide through standard teaching approaches and environmental design.

The third pattern involves sensory seeking where children actively pursue intense sensory experiences to satisfy nervous systems craving input, constantly moving, touching, making noise, or engaging in behaviors that provide proprioceptive or vestibular stimulation their brains require for organization and regulation. These children might constantly fidget, rock, spin, crash into things, chew on non-food items, make repetitive sounds, touch everything around them, or struggle to maintain still bodies during activities requiring sustained attention in seated positions without movement breaks. Teachers often misinterpret sensory seeking as hyperactivity, deliberate disruption, or inability to follow rules because these children seem unable or unwilling to sit still and keep hands to themselves during instruction, when actually their nervous systems genuinely need movement and tactile input to remain alert and regulated rather than seeking attention or deliberately violating expectations. Many sensory seekers show significant improvement when provided appropriate movement breaks, fidget tools, heavy work activities, or flexible seating options that allow them to satisfy sensory needs while still participating in learning rather than requiring stillness that their nervous systems cannot sustain without becoming dysregulated.

What Sensory Meltdowns Look Like Versus Behavioral Tantrums

Teachers must distinguish between sensory meltdowns representing complete nervous system overwhelm versus behavioral tantrums involving conscious attempts to escape demands or obtain desired outcomes, because these situations require dramatically different responses and mishandling sensory meltdowns through behavioral approaches can traumatize children while reinforcing their belief that adults do not understand their struggles or care about their distress. Sensory meltdowns occur when cumulative sensory input exceeds a child’s nervous system capacity to process and regulate responses, like a computer crashing when too many programs run simultaneously—the child completely loses capacity for rational thought, emotional control, or behavioral choice as primitive brain regions take over survival responses designed to escape overwhelming threat regardless of social consequences or long-term thinking. During sensory meltdowns, children genuinely cannot calm down through willpower alone, follow directions, process verbal information, or make choices about their behavior no matter how much they want to comply or how severe threatened consequences become, because the thinking parts of their brains have gone offline leaving only reactive survival responses operating.

Several distinctive features help identify sensory meltdowns versus behavioral tantrums. Sensory meltdowns typically occur in response to specific sensory triggers or as culmination of prolonged sensory stress even when situations seem calm to observers who cannot perceive sensory overload children experience internally, whereas behavioral tantrums usually connect more obviously to denied requests, demands children want to avoid, or desired items they cannot access. Sensory meltdowns demonstrate physiological markers of genuine distress including dilated pupils, rapid breathing, increased heart rate visible through flushed face or neck, sweating, and complete dysregulation suggesting fight-or-flight activation, whereas behavioral tantrums often show more controlled quality with children monitoring adult responses, modulating intensity based on whether tactics seem effective, and demonstrating capacity to stop or start based on circumstances in ways proving cognitive control remains intact. Sensory meltdowns typically require significant time for children to fully recover even after triggering situations end, with children appearing exhausted, disoriented, or emotionally fragile for extended periods suggesting genuine nervous system overwhelm occurred, whereas behavioral tantrums typically resolve relatively quickly once children obtain desired outcomes or accept situations will not change and might as well move forward.

Most tellingly, sensory meltdowns show no improvement or actually worsen when adults implement typical behavioral responses like ignoring attention-seeking behavior, delivering consequences, or insisting children comply before receiving support, because these approaches increase distress when applied to already overwhelmed nervous systems rather than teaching children that tantrums do not work as manipulation tactics. A child experiencing sensory meltdown who is told they must calm down before leaving an overwhelming situation, complete work before accessing sensory break space, or face consequences for their behavior will likely escalate further because their nervous system has already exceeded capacity and additional demands or threats only pile more stress onto an already overloaded system. Conversely, behavioral tantrums typically do respond to strategic ignoring of attention-seeking elements, clear limits, and consequences that demonstrate desired outcomes will not materialize through inappropriate behavior, proving cognitive control exists even if children initially resist when adults implement boundaries. Teachers who carefully track patterns usually can distinguish these situations relatively easily once they understand what differentiates them, though some children may demonstrate both sensory meltdowns in certain contexts and behavioral tantrums in others, requiring nuanced analysis to determine appropriate responses for each specific situation.

Practical Assessment Strategies for Identifying Sensory Processing Challenges

Teachers can employ several straightforward assessment strategies to determine whether concerning behaviors likely stem from sensory processing challenges requiring accommodation rather than behavioral issues requiring consequences and skill-building. The most valuable approach involves systematic observation tracking when, where, and under what circumstances difficulties occur, specifically noting environmental factors present during problem situations including noise levels, lighting conditions, temperature, crowding, visual complexity, transitions, activity types, materials involved, and time of day, because sensory processing challenges almost always show predictable connections to specific sensory contexts whereas behavioral issues demonstrate more variable patterns influenced by social dynamics, task demands, motivation, and supervision factors beyond purely sensory characteristics. Maintain detailed observational notes over several weeks recording antecedents before concerning behaviors, descriptions of what occurred, and consequences that followed each incident, then analyze patterns to identify whether difficulties cluster around sensory features or other variables that suggest behavioral rather than sensory origins.

The second valuable strategy involves informal sensory experiments where you systematically modify suspected sensory variables to observe whether changes impact behavior, essentially conducting single-subject research within your classroom to test hypotheses about what drives difficulties. If you suspect auditory over-responsivity, allow the child to wear noise-canceling headphones during suspected trigger times and observe whether behavior improves, then remove headphones during similar activities to see if difficulties return, establishing whether auditory input genuinely influences behavior or whether other factors drive concerns. If you suspect sensory-seeking behavior underlies constant fidgeting and movement, provide a wobble cushion, fidget tools, or scheduled movement breaks while maintaining identical behavioral expectations and academic demands, then observe whether accommodation helps the child meet expectations more successfully without changing anything except sensory input availability. These informal experiments provide powerful information about whether sensory accommodation addresses root causes versus whether behavioral interventions targeting choices and consequences prove necessary, allowing you to adjust support approaches based on actual evidence from your specific student rather than guessing about underlying mechanisms.

The third assessment strategy involves collaborating with parents to understand how children function across different environments and gathering developmental history that might reveal sensory processing patterns extending beyond school settings. Children with sensory processing challenges typically show similar difficulties across multiple contexts including home, community activities, medical appointments, and social situations beyond school, whereas behavioral issues often manifest more selectively in situations involving particular demands, reduced parental supervision, or specific social dynamics not present in all environments. Parents may report that their child has always been sensitive to tags in clothing, avoids certain food textures, struggled during haircuts or nail trimming, showed extreme distress during infant swimming lessons, or demonstrated other early developmental patterns suggesting sensory processing differences predating current school concerns. Several screening checklists for sensory processing can help structure conversations with parents about whether sensory patterns appear across settings and sensory systems, providing additional data points beyond your classroom observations to inform hypotheses about whether sensory processing challenges contribute to concerning school behaviors requiring occupational therapy evaluation and sensory-based intervention approaches.

Questions to Ask When Behavior Concerns Emerge

Does the behavior occur predictably in specific sensory contexts such as transitions to loud spaces, during activities involving particular textures or smells, when fluorescent lights hum, during highly visual or chaotic activities, or after extended periods without movement breaks? If yes, sensory processing may contribute significantly.

Does the child seem genuinely distressed during concerning behaviors rather than demonstrating calculating or defiant quality to their actions, and do they express confusion or remorse afterward suggesting they experienced situations as beyond their control? If yes, consider sensory processing as primary driver.

Have behavioral interventions been implemented consistently for adequate time periods yet produced minimal improvement or actually worsened the situation through added pressure and consequences? If yes, you may be applying behavioral approaches to sensory challenges requiring different support.

Do parents report similar sensory-related challenges at home, during community outings, or throughout early development including feeding difficulties, clothing sensitivities, grooming challenges, or movement-seeking behaviors? If yes, sensory processing differences likely extend beyond school context.

When you provide sensory accommodations like noise-canceling headphones, fidget tools, movement breaks, or modified activities, does behavior improve significantly even though behavioral expectations and consequences remain constant? If yes, sensory modifications address root causes effectively whereas behavioral strategies alone cannot.

Creating Sensory-Friendly Classrooms That Support All Learners

Once teachers recognize sensory processing challenges as legitimate neurological differences rather than behavioral choices, numerous evidence-based classroom modifications can dramatically improve outcomes for affected students while typically benefiting entire classes since most children appreciate reduced sensory demands and increased movement opportunities even if their nervous systems process information typically. Environmental modifications represent the foundation of sensory-friendly classrooms, beginning with careful attention to lighting quality since fluorescent lights both emit visible flickering that bothers many children and produce high-pitched humming that children with auditory sensitivities hear acutely while adults may not perceive at all. Consider using natural light whenever possible, supplementing with floor lamps or desk lamps using incandescent or LED bulbs rather than relying entirely on overhead fluorescents, allowing affected children to wear ball caps or sit under dimmed areas when bright light becomes overwhelming, and installing occupancy sensors so lights turn off automatically in unoccupied spaces rather than remaining on constantly throughout the school day creating continuous low-level sensory stress that accumulates over time.

Acoustic modifications prove equally important given that classroom noise represents one of the most significant sensory stressors for children with auditory over-responsivity while insufficient auditory input may prevent under-responsive children from maintaining alert arousal states. Reduce ambient noise through carpeting, fabric wall hangings, acoustic ceiling tiles, felt pads under chair and desk legs, and tennis balls on chair feet, creating quieter baseline environment that benefits everyone while particularly helping auditory-sensitive students whose nervous systems cannot filter background noise effectively leaving them constantly distracted by sounds others do not consciously notice. Designate a quiet corner equipped with noise-canceling headphones, soft lighting, comfortable seating, and calming visual elements where any student can retreat briefly when feeling overwhelmed without requiring permission or explanations, normalizing sensory breaks as appropriate self-regulation strategy rather than special accommodation requiring justification. Provide visual schedules showing daily routines with pictures or symbols so students know what to expect without needing to constantly monitor auditory environment for transitions, reducing anxiety associated with unpredictability that compounds sensory challenges when children must maintain constant vigilance about when changes will occur.

Movement accommodations prove essential for sensory-seeking students whose nervous systems require proprioceptive and vestibular input to maintain regulation, though all children benefit from opportunities to move throughout extended school days that demand sustained seated attention beyond what developing nervous systems can comfortably provide. Implement flexible seating options including wobble cushions, exercise balls, standing desks, floor cushions, rocking chairs, and bean bags allowing students to choose seating that supports their current regulation needs rather than requiring identical postures for all learners throughout entire days regardless of individual differences. Schedule frequent brief movement breaks using activities like jumping jacks, wall pushes, yoga poses, or dancing to songs between academic tasks, recognizing that even two-minute movement breaks can reset attention and regulation for subsequent learning periods more effectively than forcing children to sustain attention beyond their neurological capacity until behavior deteriorates requiring far longer recovery time. Create legitimate classroom jobs involving movement like delivering messages to office, collecting materials from other classrooms, or organizing supplies that provide opportunities for children needing movement input to satisfy sensory needs productively rather than through disruptive behaviors emerging when internal sensory needs go unmet during prolonged static positioning.

Responding Effectively When Sensory Meltdowns Occur

Even with excellent sensory accommodations and environmental modifications, some children will occasionally experience sensory meltdowns when unexpected situations arise, accumulated stress exceeds their current capacity despite everyone’s best efforts, or developmental immaturities in sensory processing simply overwhelm their regulation abilities temporarily. Teachers must respond to sensory meltdowns completely differently than behavioral tantrums, prioritizing safety and nervous system regulation over behavioral accountability or lesson continuation, recognizing that attempting to address behavior during meltdowns proves not only ineffective but actively harmful by increasing distress when children most need compassionate support allowing recovery. Your primary goal during sensory meltdowns involves helping children’s nervous systems return to baseline regulation as quickly as possible through reduced sensory demands, access to calming strategies, and emotional co-regulation where your calm presence helps their dysregulated systems reorganize, similar to how you might support someone experiencing panic attack by staying calm, reducing stimulation, and waiting patiently for their nervous system to naturally return to regulated state rather than demanding they immediately pull themselves together through willpower.

Practical meltdown response begins with immediately reducing sensory demands by moving child to quieter, less stimulating environment if possible or reducing environmental stimulation if child cannot move safely, including dimming lights, decreasing noise, removing audience if other children are watching, and stopping all non-essential demands or expectations that pile additional stress onto already overwhelmed nervous system. Speak minimally using simple calm words rather than lengthy explanations, reasoning, or consequences the child cannot process during dysregulation, offering choices only if child demonstrates capacity to think clearly enough to make decisions rather than forcing choices that increase distress when thinking brain remains offline. Offer but do not force sensory regulation strategies the child has previously found helpful such as heavy pressure through weighted blanket or firm hugs if child enjoys pressure, access to fidget tools or stress balls, movement like rocking or pacing if child finds that organizing, or quiet space with minimal stimulation if sensory overload triggered meltdown. Stay physically close providing calm non-verbal presence that communicates safety without demanding interaction, remembering that your regulated nervous system can help child’s dysregulated system reorganize through biological co-regulation even without words or direct intervention.

After immediate crisis passes and child returns to calmer state, provide time for full recovery before expecting return to academic demands or addressing behavioral aspects of situation, recognizing that nervous system recovery requires significantly longer than surface appearance might suggest and pushing children back into demands prematurely often triggers secondary meltdowns as still-fragile nervous systems cannot sustain expectations requiring regulation reserves not yet restored. Save conversations about what happened, problem-solving alternative responses, or planning prevention strategies for much later when child has completely recovered and can engage thinking brain productively, potentially discussing during recess time, end of day, or even following day rather than immediately after meltdown when processing capacity remains impaired. Document meltdown patterns noting triggering contexts, warning signs observed before full meltdown emerged, strategies that helped or did not help recovery, and duration required for child to return to full functioning, using this information to identify patterns suggesting prevention approaches, environmental modifications that might eliminate triggers, or accommodations that could reduce frequency and intensity of future meltdowns. Communicate with parents and potentially occupational therapy professionals about recurring meltdown patterns, collaborating to ensure consistent support approaches across contexts and consideration of whether formal evaluation or additional therapeutic support might benefit this student’s sensory processing development and regulation capacity.

Collaborating With Parents and Building Sensory Support Teams

Effective support for students with sensory processing challenges requires close collaboration between teachers, parents, and potentially additional professionals including occupational therapists who specialize in sensory integration, school psychologists who understand how sensory processing affects learning and behavior, administrators who can authorize necessary accommodations and environmental modifications, and special education staff if sensory challenges qualify students for individualized education plans or 504 plans providing formal protections and required supports. Parents represent absolutely critical partners in this collaboration since they know their children more deeply than any professional ever will, have observed sensory patterns across developmental periods and diverse contexts, understand what strategies work or do not work at home, and can provide historical information about early sensory differences that help contextualize current school challenges. Many parents of children with sensory processing challenges have spent years advocating for recognition that their children’s difficulties represent genuine neurological differences rather than defiance or poor parenting, potentially arriving at school partnerships feeling defensive from previous negative interactions with professionals who dismissed their concerns or blamed parenting for sensory-based behaviors, so approach these conversations with genuine curiosity, respect for parent expertise, and openness to learning about this individual child’s unique sensory profile rather than approaching from expert position assuming you know better than parents what drives their child’s behavior.

Initiate parent collaboration by sharing specific observed patterns showing when and where difficulties occur alongside tentative hypothesis that sensory processing may contribute, explicitly framing this as question rather than diagnosis since only qualified professionals can formally identify sensory processing disorders, while asking parents whether they have noticed similar patterns at home or in other settings beyond school. Many parents will respond with relief that finally someone recognizes their child’s struggles as potentially neurological rather than behavioral, possibly sharing extensive observations about early feeding difficulties, clothing sensitivities, responses to grooming activities, reactions to various sensory experiences, and patterns showing sensory challenges extend far beyond school context. Other parents may need time processing this new framework for understanding behavior they have attributed to other causes, requiring patient education about sensory processing differences, what they look like in children, how they differ from behavioral issues, and why recognizing them matters for effective support. Share resources about sensory processing including websites, articles, and books that help parents understand what you are observing, while emphasizing that sensory challenges represent neurological differences rather than disorders requiring dramatic intervention, with most children responding well to environmental accommodations and regulation strategies rather than requiring intensive therapy or significantly restricting activities.

Work with parents to develop consistent approaches across home and school contexts so children receive similar sensory supports rather than managing completely different expectations and accommodations depending on setting, reducing confusion and improving generalization of regulation strategies across environments. Discuss sensory tools that help at home and could be replicated at school, movement activities parents use successfully to help child regulate before homework or bedtime routines, calming strategies effective during weekend outings or family events, and warning signs parents notice before sensory overwhelm reaches meltdown levels that might help you identify similar patterns allowing intervention before crisis points. Consider whether formal occupational therapy evaluation might benefit this child’s sensory processing development, recognizing that OTs specialize in assessing sensory processing patterns, designing individualized sensory diets providing optimal sensory input throughout days, recommending specific accommodations addressing individual sensory profiles, and directly teaching regulation strategies helping children manage their sensory processing differences more effectively over time. Many schools employ occupational therapists who can evaluate students and provide consultation to teachers about classroom modifications, while some families pursue private occupational therapy providing more intensive intervention if school-based services prove insufficient for this child’s particular needs.

Teaching Self-Awareness and Self-Advocacy: Long-Term Success Skills

While environmental accommodations and adult support prove essential for children currently struggling with sensory processing challenges, equally important involves teaching children to recognize their own sensory patterns, understand what helps them regulate, and advocate for needs appropriately as they mature toward eventual independent management of sensory differences extending into adolescence and adulthood when external supports may not always be available or appropriate. This self-awareness development begins with teaching children vocabulary for describing sensory experiences and regulation states, moving beyond generic “good” or “bad” feelings toward specific awareness of whether they feel overwhelmed or under-stimulated, which sensory systems need adjustment, what types of input help versus hinder current regulation, and how different environments and activities affect their nervous system functioning throughout days. Use simple check-in systems like zones of regulation colored charts, emotion thermometers, or numeric scales helping children quantify internal states and communicate needs to adults who cannot observe internal sensory experiences directly, practicing these check-ins regularly during calm periods so children develop habit of monitoring internal states rather than waiting until meltdowns occur to notice nervous system dysregulation requiring intervention.

Explicitly teach children connections between sensory experiences and behavioral responses they notice occurring automatically, helping them understand that when cafeterias feel overwhelmingly loud their bodies naturally trigger escape responses not because they are bad but because nervous systems interpret situations as threatening even when intellectually they know lunch is safe. This neurological education reduces shame many children feel about sensory differences making them feel broken or wrong, reframing sensory processing challenges as neutral differences requiring accommodation similar to wearing glasses for vision differences rather than character flaws requiring fixing through willpower alone. As children develop this understanding, involve them increasingly in problem-solving accommodations that might help manage sensory challenges, asking what tools they have noticed helping, which environments feel easier versus harder, what warning signs they notice before becoming overwhelmed, and what strategies they want to try for managing difficult situations more successfully. This collaborative approach builds investment in using accommodations rather than resistance children may demonstrate when adults impose supports without their input, while simultaneously teaching critical thinking about personal needs and creative problem-solving that will serve them throughout lives managing sensory processing differences.

Distinguishing sensory processing challenges from behavioral issues represents perhaps the most critical skill teachers can develop for supporting the increasingly neurodivergent student populations filling today’s classrooms, because correctly identifying root causes determines whether interventions help or harm struggling children while dramatically affecting whether concerning behaviors improve over time versus continuing or worsening despite everyone’s dedicated efforts. Sensory processing challenges involve involuntary neurological responses to sensory information that overwhelms, under-stimulates, or requires intense seeking behavior to satisfy nervous systems processing information atypically compared to neurotypical peers, manifesting through three primary patterns including sensory over-responsivity where children experience stimuli more intensely than others, sensory under-responsivity where children require stronger input to register sensations peers notice easily, and sensory seeking where children constantly pursue intense sensory experiences their nervous systems require for organization and regulation. These neurological differences look dramatically different from behavioral issues involving conscious choices children make even if those choices stem from inadequate skills or emotional regulation, responding completely differently to interventions with sensory challenges requiring environmental modifications and regulation support rather than behavioral consequences and skills instruction that prove not only ineffective but actively harmful when applied to involuntary neurological responses children cannot control through willpower alone. Teachers can identify sensory processing challenges through systematic observation noting whether difficulties occur predictably in specific sensory contexts, tracking whether traditional behavioral interventions produce improvement or worsen situations, assessing whether children demonstrate genuine confusion and distress about their responses versus calculating quality suggesting conscious choice, collaborating with parents about patterns extending beyond school into home and community settings, and conducting informal experiments where sensory accommodations are provided while behavioral expectations remain constant to determine whether modifications address root causes effectively. Once sensory processing challenges are recognized, numerous evidence-based classroom modifications dramatically improve outcomes including reduced sensory demands through improved lighting and acoustics, movement opportunities through flexible seating and scheduled breaks, access to sensory tools like fidgets and weighted materials, quiet spaces for regulation when needed, and visual supports reducing reliance on auditory processing for expectations and transitions. When sensory meltdowns occur despite accommodations, effective response prioritizes safety and nervous system regulation through reduced demands and calm supportive presence rather than behavioral accountability or consequences applied during dysregulation, recognizing that children’s thinking brains have gone offline leaving only survival responses requiring compassionate support allowing recovery before any behavioral discussions or problem-solving can occur productively. Long-term success requires teaching children self-awareness about sensory patterns, vocabulary for communicating needs, understanding that sensory differences represent neutral neurological variations rather than character flaws, and self-advocacy skills allowing increasingly independent management of sensory processing challenges extending into adolescence and adulthood, ultimately helping children understand themselves better while providing accommodations supporting success rather than continuing punitive cycles that damage self-esteem while failing to improve outcomes when behavioral strategies are mistakenly applied to neurological challenges requiring completely different support approaches recognizing sensory processing as legitimate difference deserving accommodation not punishment.